From I Paid Hitler, by Fritz Thyssen: In order to allay discontent, Hitler conceived of a new idea. Every German shall own his car. He asked industry to devise a popular car model to be built at such a low price that millions could buy it. The Volkswagen (People's Car) has been talked of for the past five years and has never been seen on the market. "These cars will be built for the new highways," said the party propagandists; "an entire family will be able to ride in one of them at 100 kilometers (60 miles) an hour." The party leaders say that the highways were built for the People's Car. But the People's Car is one of the most bizarre ideas the Nazis ever had. Germany is not the United states. Wages are low. Gasoline is expensive. German workers never dreamed of buying a car. They cannot afford the upkeep; to them it is a luxury.

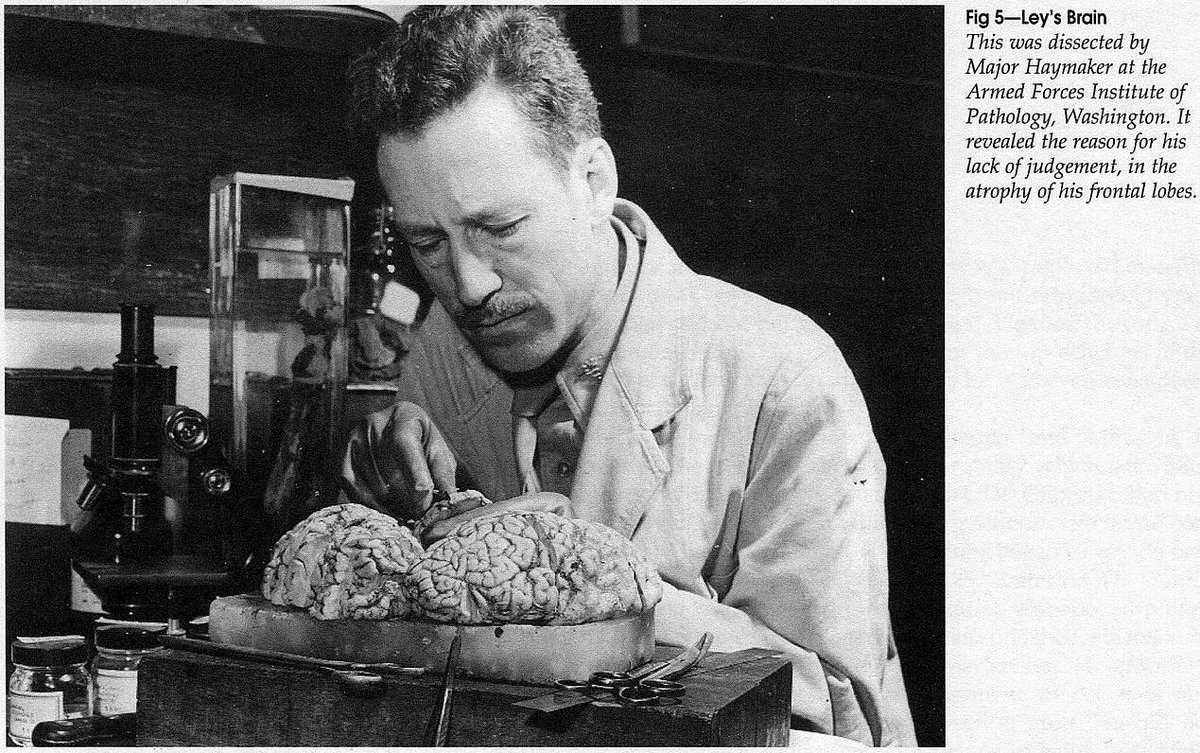

Dr. Ley, the stammering drunkard who is the chief of the German Labor Front. He controls the four to five hundred million marks paid in every year by the German workers as dues to the Labor Front. I do not say that he puts all this money into his own pocket. But the figure has certainly turned his head.

He had an automobile factory built for the production of the People's Car. On this occasion he invented a brand new form of knavery. The future buyers of the People's Car were invited to buy it in advance, by making predelivery installments. This is the reverse of the credit installment system. The system shows genius. Ley pocketed about a hundred million marks when the war came because the People's Car factory now had to produce tanks and motorcycles for the army.

From Nuremberg Diary, by Gustave M. Gilbert Ph.D. (Formerly Prison Psychologist at the Nuremberg Trial of the Nazi War Criminals):

I visited Robert Ley with the prison psychiatrist the-day before Ley killed himself. He was in an agitated state, pacing up and down his cell' in his felt boots and G I field jacket, which some of the prisoners were wearing at that time. Asked how he was getting along in preparing his defense after reading the indictment, he hunched) into a tirade:

How can I prepare a defense? Am I supposed to defend myself against all these crimes which I knew nothing about? If after all the bloodshed of this war some more sacrifices are needed to satisfy the vengeance of the victors, all well and good—" (Here he placed himself against the wall, crucifix-like, and declaimed with a dramatic gesture) "Stand us against a wall and shoot us!—All well and good—you are the victors. But why should I be brought before a Tribunal like a c—, c—, like a c—, c—?" He stammered and blocked completely at the word "criminal" until I supplied it, then added: "Yes, I can't even get the word out." He repeated this trend of thought several times, pacing up and down the cell, gesticulating and stuttering in great agitation.

The next night he was found strangled in his cell. He had made a noose from the stripped edges of an army towel tied together and fastened to the toilet pipe. In his suicide note he said that he could not stand the shame any longer.

Ley's suicide created considerable consternation in the prison detachment. The guard was quadrupled so that there was one sentry on each cell 24 hours a day. For fear of suggesting to the other defendants how to commit suicide, Colonel Andrus, prison commandant, did not reveal immediately what had happened, but circulated an ambiguous note a few days later, announcing Ley's death.

I was sitting in Goering's cell when this note was brought around on October 29. He read the announcement without any show of emotion. After the officer left the cell, he turned to me:

"It's just as well that he's dead, because I had my doubts about how he would behave at the trial. He's always been so scatterbrained—always making such fantastic and bombastic speeches. I'm sure he would have made a spectacle of himself at the trial Well, I'm not surprised that he's dead, because he's been drinking himself to death anyway . . . "

Similar attitudes were expressed by the other defendants. The only one who seemed to mourn Robert Ley's passing at all was the vulgar fanatic, Julius Streicher. The eccentric labor leader, who had forced German workers to subscribe to Streicher's journal, Der Stuermer, had been the only one who had seen fit to associate with Streicher during their previous internment in Mondorf prison camp. However, Streicher thought it was cowardly of Ley to commit suicide and leave behind a "Political Testament" calling the Nazi anti-Semitic policy "a big mistake."

10/24/1945 Robert Ley commits suicide in Allied captivity. His suicide note reads (in part):

"Do I have a right to appeal to the German people after its singular catastrophe? I have always been one of the responsible men. I have been one of the responsible men, I was with Hitler in the good days, during the fulfillment of our plans and hopes and I want to be with him now in the black days. I wanted to be with him in the black days. God led me in whatever I did. He led me up and now he lets me fall. I am torturing myself to find the reasons for my downfall, and this is the result of my contemplation's.

We have forsaken God and therefore were forsaken by God. Anti-Semitism distorted our outlook and we made grave errors. It is hard to admit these mistakes but the whole existence of our people is in question. We Nazis must have the courage to rid ourselves of Anti-Semitism. We have to declare to our youth that it was a mistake. The youth will not believe our opponents. We have to meet the Jews with open hearts. German people, reconcile yourselves with the Jew. Invite him into your home with you. We cannot stop the excited sea at once but must let her calm down gradually, otherwise terrible repercussions would result. A complete reconciliation with the Jews has priority over economic or cultural reconstruction. We outspoken Anti-Semites have to become the first fighters for the new ideas. We have to show the people the way.

Should Germany solve the Jewish problem, and grow healthy through it, the whole world would benefit from it. This most burning problem of the world would be solved once and for all. Zionism in its present form is not a permanent solution. Germany is ripe to solve the Jewish problem. German anti-Semitics have taken the first step. They have to take the second step, too. Jewry has to reconcile herself with Germany and vice versa, for the sake of world peace and of world welfare. Not an armistice, but a peace built on logic, knowledge, clear rights and obligations is necessary. The Jew should make a friend out of Germany. . . .

Here, the outspoken anti-Semites have to become the first fighters for the new and yet so close idea. . . . God has taught me that in my cell in Nuremberg, and now my plan:

A) First, the creation of a board of Jews and anti-Semites, honestly prepared to travel this road and to find the conditions under which Jews and Germans can live together.

B) An executive committee, again Jews and Germans together, to execute the agreed-upon arrangements.

C) An organization for re-education and propaganda to disseminate these ideas down to the smallest village. . . . .

I am not admitting a mistake, but. . . . I am merely coming to a logical conclusion. . . . One must have been an anti-Semitic to come to this further step of knowledge. This is why only you, my German people, may dare to invite the Jews to make their future home with you . . . Hate and love lie close together . . . . Is the Jew prepared to go along? If he is intelligent—yes. If not, then I cannot change that. At least I have done my duty by showing humanity the road. God showed me. If the Jew refuses my plan, then the depicted world-catastrophe will take its inevitable course."

From Justice at Nuremberg, by Robert E. Conot: Upon the collapse of the Reich, Ley toyed with suicide, but fumbled an attempt to shoot himself and lacked the courage to take poison. On May 16, a detachment of the 101st Airborne Division, acting on a tip, discovered him in a mountain cabin south of Berchtesgaden. An incipient beard sprouting on his face, he insistently stammered out that he was not Ley, but Dr. Ernst Distelmeyer. He had been asleep when the troops burst in and was hustled off wearing blue pajamas, over which he threw a woolen cape. On his balding head was perched a green Tyrolean hat. "Distelmeyer," he kept repeating at his initial interrogation when asked his name, until suddenly party treasurer Franz Xavier Schwarz was brought into the room.

"Well, Dr. Ley, what are you doing here!" Schwarz burst out.

At Mondorf he was issued an ill-fitting jacket and pair of trousers. As soon as he arrived at Nuremberg, he addressed a letter to "Sir Henry Ford," suggesting that Ford take over production of the Volkswagen and make him the manager of the plant. All during the month of September he was left, except for one interrogation by Amen, to ruminate in his cell. His feverish brain, which had suffered some slight damage because of his drinking and a World War I injury, would not let him rest, and he filled scores of sheets of paper with his writing. He entitled a seventy-four-page autobiography "The Fate of a Peasant." A lengthy political treatise received the caption "Life or Glory."

"I must go on America's side, and America must help us in her own interest against the Asian flood," he wrote. Germany had to become part of the American commonwealth, and National Socialism must be purged of anti-Semitism.

He spent a great part of his time in communion with his dead wife Inge, and hallucinated that she visited his cell: "You are bodily near to me. I am feeling you. You are embracing me with your love, your charm and your beauty. Illegirl, how beautiful you were! Beautiful in body, soul and spirit. You were a rare creation of our Lord. . . . She is silent, I lose myself in meditation, finally in a deep relaxing sleep and dream: Germany would have become so beautiful, Strength Through Joy, the most beautiful cities and villages had been planned, just wages, a great unique health program, social security for the aged, road construction and traffic lanes—how beautiful Germany could have been if, if, if, and always again if. God in heaven what have I done that I am treated under such conditions as a criminal. Lord God, give me an answer, I have a right to it."

Attempting to reconcile the Nazi disaster with his fanatic faith in the Fuehrer, Ley told Major John J. Monigan, his interrogator: "I wish to say at this time that the Fuehrer was one of the greatest men there ever was. But one thing broke us, that was our Willensetbos [the belief that anything could be accomplished if it were willed powerfully enough] and our anti-Semitism, which were the things that finally undid us.">

In his political testament addressed to the German people, Ley expatiated: "We deserted God and so God deserted us. In place of His divine grace we substituted our human will, and in anti-Semitism we violated one of the principal laws of His creation. Looking back upon all this today, I know and could recount dozens of examples how paralyzing and actually disastrously these two factors influenced us. The anti-Semitic spectacles upon the nose of bold and defiant men were a disaster. This must for once be courageously admitted. It is to no avail to evade the issue. Certainly, it is bitter and hard to admit mistakes. It is not enough to say we will no longer talk about anti-Semitism, we will tolerate the Jews, we are forced to do so. No, we must take the step completely, half steps are no good. We must eliminate suspicion and meet the Jew with an open heart. Judaism must make its peace with Germany, and Germany must make its peace with Judaism in the interest of world peace and world prosperity. Hatred and love dwell in close proximity."

A few days later, on October 19, Ley, together with the other defendants, was presented with the indictment, charging him with "Formulation of a common plan or conspiracy to commit Crimes Against Peace: Namely, planning, preparation, initiating or waging a war of aggression, or a war in violation of international treaties; War Crimes: Namely, violation of the law or customs of war [including] murder, ill treatment, deportation, the forced labor of civilian populations, the murder and maltreatment of prisoners of war or hostages, the plunder of private or public property, and the wanton destruction of towns or villages; Crimes Against Humanity: Namely, murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation, and other inhumane acts committed against any civilian population, before or during the war, or persecutions on political, racial or religious grounds . . . whether or not in violation of the domestic law of the country where perpetrated."

For the next half-dozen days, Ley, bewildered like his fellow prisoners by the omnibus "conspiracy" charge, wrote tirelessly in sanctimonious self-justification: "I understand that the victor thinks that he has to exterminate his hated opponent. I'm not defending myself against this—that he wants to shoot or kill me. I defend myself only against his endeavor to stamp me as a criminal. The war fitted into my plans like hail into a corn field. There is no question of a conspiracy or a common plan. The Fuehrer, according to his habit, never spoke with anybody about things which didn't concern him. I always heard about the beginning of an operation out of newspapers or over the radio."

Disturbed and erratic, he paced up and down in his cell, gesticulating and muttering. To Gilbert and Dr. Kelley, he complained bitterly: "How can I prepare a defense? Am I supposed to defend myself against all these crimes which I knew nothing about?" Turning against the wall, he flung his arms out dramatically in the form of a cross, and cried: "Shoot me! Shoot me now as a German. You are the victors! But why should I be brought before a tribunal like a k-k-k-k-k-k . . ." he was unable to get the word "Kriminal" out of his mouth.

He became obsessed with the idea of martyrdom. His death would demonstrate that his motives were pure. If the Americans would not kill him, then perhaps he would kill himself. "Farewell. Farewell," he recorded. "I cannot stand this shame any longer. Physically, nothing is lacking. The food is good. It is warm in my cell. The Americans are correct and partially friendly. Spiritually, I have reading matter and write whatever I want. I receive paper and pencil. They do more for my health than necessary, and I may smoke and receive tobacco and coffee. . . . I am reconciled with God. I implore his mercy and his pity and I pray for it sincerely. Now comes sweet death, savior of all my suffering. To my Inge and to my Führer."

Since Conti's death, precautions against suicide had been increased—at night the chairs were removed from the cells, and in daytime it was forbidden to place them against the wall. But, at quarter to eight on the night of October 25, Ley tore the edge off a GI towel, soaked it in toilet water, and tied it around the toilet pipe that ran up the wall. Ripping some pieces from his underwear, he stuffed them into his mouth. He then looped the towel around his neck, twisted himself several times so that it tightened and cut off the circulation, and, in the process of losing consciousness, collapsed onto the toilet.

Through the opening in the door, only a prisoner's legs were visible when he sat in the recessed toilet alcove. Each guard was responsible for four cells. At 8:10 PM, when the corporal of the guard came by to collect the prisoners' eyeglasses, the sentinel had passed by Ley's door on four leisurely rounds, during which Ley had apparently not moved. To the demand by the corporal for Ley's glasses, there was no response. The corporal unlocked the door. Ley, his arms and head dangling limply, was suspended grotesquely by the towel. Though Dr. Pfluecker administered a heart stimulant and attempted artificial respiration for twenty minutes, Ley could not be revived. After an autopsy was performed, his body, placed in a box lined with butcher paper, was taken that same night to the Nuremberg cemetery, where it was interred in an unmarked grave.

Twitter: @3rdReichStudies FB: Horrific 20th Century History