A Political commentator recently termed the Strait of Gibraltar the "Gate to the Sea of Destiny."

It is very possible that this poetic term is actually a prophetic term. The Mediterranean Sea might well become a "Sea of Destiny" for the nations of Europe, if they should find a way to unite—not politically which is not to be expected, but economically—to meet the problems that will face them only a few decades hence. It is not a great novelty if one states that Europe needs room for expansion. But it is a novelty how this expansion might be accomplished. Professor Hermann Soergel of Munich, a broadminded economist with ambitions that expand into the realm of the engineering sciences, has recently published a number of suggestions that were shocking on account of their magnitude as well as of their feasibility. It is nothing less than a new and improved continent which he proposes, a continent he wishes to be termed Atlantropa.

Atlantropa, etymologically a combination of Atlantis and Europa, is to be a very tangible actual combination of Africa and Europe, achieved by means of a solid wall from Southwest Spain to the vicinity of Africa's Atlas mountains. It is a wall to close the gate to the Mediterranean Sea, a dam across the Strait of Gibraltar.

The purpose of such a dam becomes obvious if one knows that the Strait of Gibraltar is not only the gate to the largest inland sea on Earth but also its very means of existence. If the Strait of Gibraltar did not exist the Mediterranean Sea would soon cease to be. Not less than 100,000 cubic yards of water flow every second from the Atlantic Ocean through the Strait of Gibraltar into the Mediterranean Sea to maintain its level.

The Mediterranean Sea has a large surface and consequently tremendous quantities of water evaporate every second since this Sea, around which our recorded history began, has a warm and sometimes even hot climate. The rivers that flow into this Sea are not very numerous and none of them is overly large (—Ebro, Rhone, Po and Nile are the four largest of them—) therefore they do not furnish the amount of water that evaporates from the Sea. Actually these rivers and the rain that falls over the Mediterranean fail to compensate evaporation losses by about 100,000 cubic yards per second, about the amount that flows through the Strait of Gibraltar. The Atlantic Ocean furnishes the water lost in the Mediterranean and it is large enough not to be seriously or even noticeably affected by this tremendous amount.

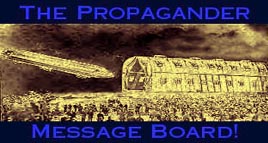

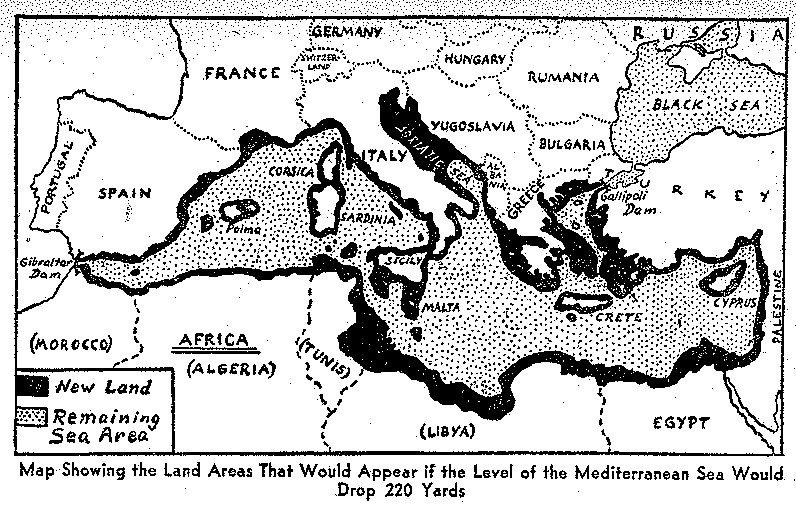

But if an earthquake were to close the Strait of Gibraltar, the level of the Mediterranean Sea would drop steadily until a status of balance is reached. This status of balance would require that the area of the sea is reduced to about half of its present size so that the other half would become dry and probably habitable land.

Geologists believe, by the way, that this status once prevailed; the Strait of Gibraltar is probably not more than 50,000 years old. If it should be true that it opened suddenly—as certain signs seem to indicate—the flooding of the Mediterranean depression must have been a catastrophe which would explain all the myths and legends of the great flood. If the Strait of Gibraltar should close with equal suddenness the level of the Mediterranean Sea would at once start to recede at the rate of about five feet two inches per year. Hermann Soergel's plan is easy to understand if one knows these facts.

To raise several hundred thousands of square miles of land from the bottom of the sea, to produce about 160 million HP of electric power, to strengthen the connection between Africa and Europe, to achieve a million other things one only has to dam the Strait of Gibraltar solidly.

Professor Soergel knows perfectly well that a dam that prevents the Atlantic Ocean from pouring a hundred thousand cubic yards of water per second into the receding Mediterranean Sea is a project of tremendous proportions. But he is also well aware of the fact that there are no impossible tasks involved. Since it would be useful to dam the Dardanelles on the other side of the Mediterranean Sea too, it would be wise to start the project at this point.

The flow through the Dardanelles amounts to less than ten per cent of the flow through the Strait of Gibraltar and since this strait would continue to function as an infill valve during the work at the Dardanelles no pressure difference would hamper the work on the first dam. At the same time valuable experience could be gathered during this work before the more difficult job at Gibraltar is actually started.

The Dam of Gibraltar should not cross the Strait at its narrowest point because it is there more than 550 yards deep. Soergel wants to build the dam between Tanger in Africa and Tarifa on the European side. It should follow a line of submerged reefs and shallow spots so that the greatest depth encountered would be only about 350 yards. The dam, arching out into the Atlantic Ocean in a wide loop would have to be about 500 yards thick at the bottom and about 50 yards at the top to withstand the terrific pressure of the water of the Ocean. There would be no flood gates because they would tend to weaken the dam.

On either side two mighty canals would lead from the Atlantic coast to the Mediterranean. One on each side would consist of a series of gigantic locks, admitting even large liners. The other two canals would lead the water to two huge water power plants, each capable of generating 80 million HP.

Similar canals and similar power plants —only on a much smaller scale—would be installed at the Dardanelles. The calculations used in Soerge’s plan are based on the assumption that there would be a level difference between Atlantic and Mediterranean of 2 00 meters (220 yards). To obtain this difference, Soergel wants to operate his power plants only on a very small scale until the level of the Mediterranean Sea has dropped by 220 yards. Then he wants to re-establish full compensation for the then occurring evaporation losses of the Mediterranean Sea again but to maintain the difference in level and to utilize every ounce of Atlantic water for the generation of power.

The plan, which had been termed "Atlantropa Plan" by Soergel himself caused much astonishment and surprise when it was published a few years ago. Everybody realized at once that it opened tremendous possibilities, but everybody also realized at once the obstacles to be overcome. The smallest of them are those that are purely technical. It is true that a dam of this size—it would have to be about 20 miles long—cannot be actually constructed with present day methods.

But there is no doubt that the technique of building it could be worked out. There is also no doubt that the necessary changes at the mouth of the rivers and of the Suez Canal could be effected without much difficulty.. There is also no doubt that the necessary gigantic locks and the tremendously large water turbines and dynamos could be built.

But there are very many other doubts. A large number of Mediterranean harbors—practically every harbor at the shores of all the countries bordering the Mediterranean Sea—would become obsolete. Almost every one of them would be many miles inland as soon as the Dam of Gibraltar is closed and the waters of the Atlantic Ocean separated from the Mediterranean. This would mean financial losses of a magnitude that cannot even be estimated. On the other hand it is certain that the gains would be so immense and so manifold that even these losses might be hardly noticeable. There is a more serious objection, however.

The bottom of the Mediterranean Sea seems to be actively volcanic. It is likely that the volcanic activity would decrease very much as soon as the weight of the water is removed. The main objections, however, are of political nature. As long as Europe is not politically, or at least commercially united there is no hope of even seriously considering the Atlantropa Plan. Soergel knows very well, of course, that under present political conditions no government and no business organization would dare to take steps towards its realization. The world in general and Europe in particular will have to change very much politically until mankind may start changing its planet geographically.

However, Soergel does not stop pointing out to the European nations that the adoption of his project would benefit even those countries that do not have direct access to the Mediterranean Sea and consequently would have no share in the new land and its products.

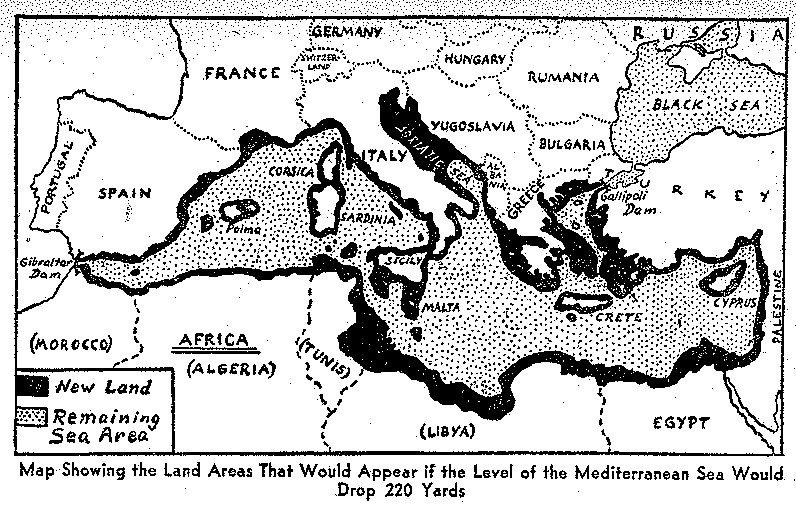

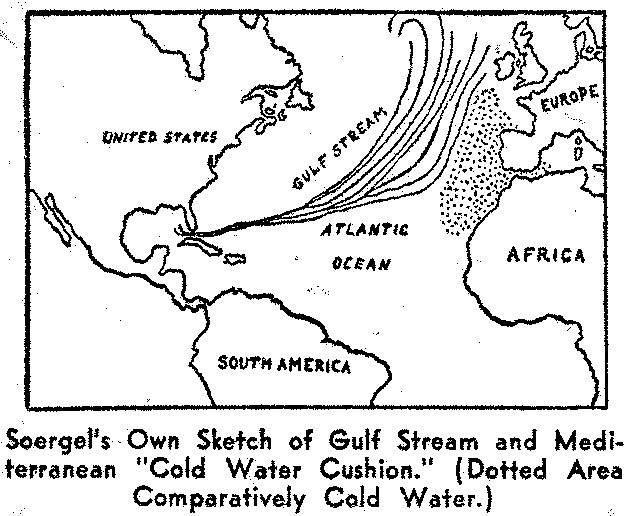

It is true that the Dam of Gibraltar would change the climate of Northern Europe in a favorable way. As everybody knows England, Northern France, the Netherlands, Northern Germany and even the Scandinavian countries benefit tremendously from the American warmth brought to their shores by the waters of the Gulf Stream. It is not so well known, however, that a great deal of warm Gulf Stream water is spent "uselessly" in the Northern Atlantic, west of Ireland. To exert all its beneficial power on the Northern parts of Europe the Gulf Stream should flow a little more toward the East than it actually does.

There have been several plans proposed to influence the course of the Gulf Stream, they were either fantastic or futile, usually fantastic and futile. These plans tried to change the direction of the Gulf Stream near its source, preferably while it passes south of Florida's Keys. That they would have failed to work even if they had been more intelligently planned was not known until recently. Scientists that investigated the data gathered about the flow of the Gulf Stream on the European side learned to their surprise that it is the Mediterranean that prevents the Gulf Stream from reaching Europe more directly. In spite of the large inward flow of Atlantic water through the Strait of Gibraltar there is a counter current of cold water near the bottom of the Strait. This counter current, spreading out far and wide as soon as it has passed the Strait, acts like a "protecting" cushion of cold water.

Assisted by Professor O. Jessen, an authority on the Strait of Gibraltar, Professor Soergel drew a sketch of prevailing conditions that shows clearly that the Gulf Stream would probably flow directly into the English Channel and thus into the North Sea, if only the Mediterranean would stop to send its cold bottom-waters into the Atlantic Ocean. A dam across the Strait, as proposed by Soergel for entirely different reasons would naturally prevent the Mediterranean from deflecting the course of the Gulf Stream. Thus climatic conditions for Europe would improve in general if the Atlantropa plan were realized.

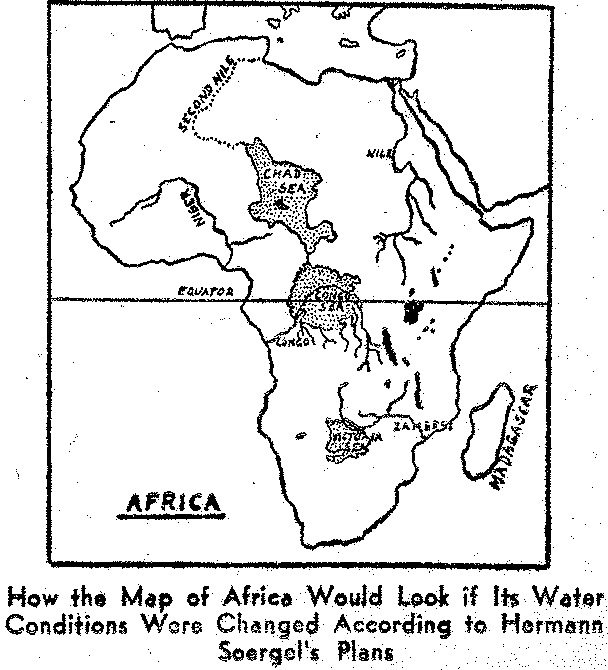

While the possibilities and the feasibility of "Atlantropa" were still hotly discussed, Soergel published another and even more interesting plan. Progressing logically from one possibility to another he investigated what could be done to Africa with a few changes of water levels. Africa and Australia are the two continents that are destined to receive the largest percentage of Earth's excess population during the next centuries if they are able to support it. Under present conditions they are not and the reasons are the same for both continents.

Life needs warmth and water but in either case only the former is present. Africa as well as Australia have a sufficiently warm climate but neither of them can boast of really large bodies of water in its interior. As far as Africa is concerned this statement may sound surprising if one thinks of the large lakes of Inner Africa like lake Victoria, Lake Nyassa and Lake Tanganyika. But it is nevertheless true. The African lakes, large as they are, do not provide enough water for the whole continent, especially because they are all situated in East Africa, i.e., because they are comparatively close together. The other parts of Africa, although they may boast mighty streams, do not possess large lakes. If Africa were to be populated extensively one might think of damming one or several of these large rivers in order to create artificial lakes of large size.

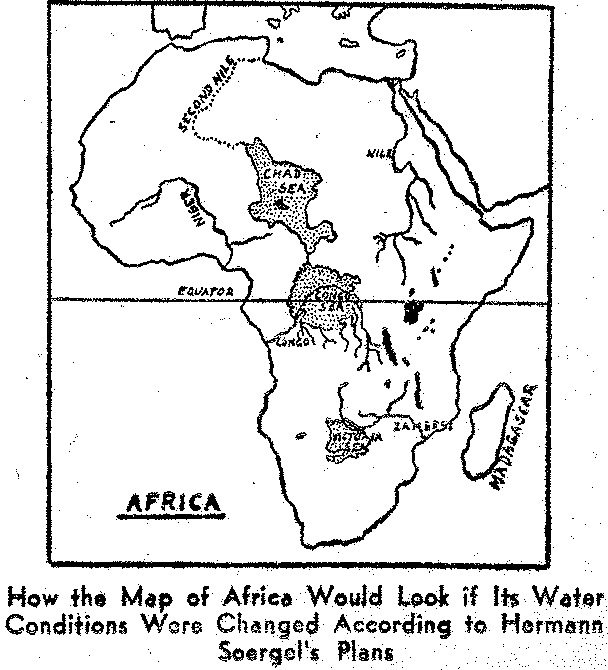

Fortunately conditions are very favorable and the technical difficulties are small. One of Africa's mightiest rivers, the Congo River, flows for more than half its entire length through a large depression of almost a million square kilometers in area. The solid mountain chains and plateaus surrounding the depression rise unbroken to about 1,500 feet above the bottom of the huge bowl.

There is only one small outlet through which the Congo River winds its way to the Atlantic Ocean. If the river would be dammed at a certain point the large depression would slowly begin to be flooded until it would represent an immense lake. Actually it was a large lake once in prehistoric times before the river had managed to gnaw its way through the rocks obstructing its flow. Needless to say that Soergel has made plans for such a dam. Needless to say also that he does not only plan a dam with which to better the Inner African climate but that his dam is to yield a large number of horsepowers by means of water turbines and generators with which it is to be equipped. A level difference of fifteen hundred feet with a large body of water on top of this height cannot very well be overlooked by a power engineer.

But what will happen if the water manages to find another way out of the gigantic natural bowl? There is a point where such an event is likely to occur. North of the "Congo Bowl" there is a second large depression, not as deep but of an even greater area than the Congo bowl. The deepest point of this depression is marked by Lake Chad. Lake Chad is without any connection with the ocean or any body of water, but it is still a large lake. Soergel now proposes to eliminate the danger of his "Congo Sea"—as he terms it—overflowing and bringing disaster to presumably populated areas by creating a high level outlet toward North near Ubangi. West of Ubangi there is a partial breach in the walls of the Congo bowl that is conveniently located.

The water of the overflowing Congo bowl is to create a second large artificial inland "sea" in the Chad depression. Even if this also were filled to capacity there would still be a considerable difference between high water levels in both "seas." The surface of the Congo Sea would be about 300 feet higher above ocean-level than that of the Chad Sea. Therefore the Congo outlet involves a drop of about 300 feet of which at least 200 can be utilized for another power plant at the North Shore of the Congo Sea.

It is not very likely that the Chad depression will be rapidly filled to capacity, not only because most of the ground is now very dry but mainly because an increased surface means also increased evaporation. But if the Chad depression does not constitute a sufficiently large reservoir for the water of the Congo River and its tributaries the northern shore of the Chad Sea might be connected with the Mediterranean Sea in utilizing an number of smaller depressions. Thus a "Second Nile" would start from the Chad Sea and flow into the Gulf of Gabes of the Mediterranean Sea. The "Second Nile" would be somewhat larger than the actual river Nile and could be travelled upon by rather large ships so that many places that are now inaccessible Inner Africa could be reached by ship directly.

Even a third large artificial inland sea is possible near the Victoria Falls of today. It would be filled by the Zambesi River that, although large, would need quite a number of years to fill this third large African depression.

How much three large artificial lakes of the size indicated by these three natural depressions would change Africa's climate is almost impossible to imagine. One can only say that the changes will be beneficial; the whole continent will certainly become much more habitable with a climate friendlier to the White race.

It is probably the second part of Hermann Soerge's Atlantropa plan, the project involving Africa alone, that may be started first. It has the advantage of requiring less labor and less capital expenditure, it hardly calls for new methods of construction and is blessed with fewer political complications.

And if of the whole Atlantropa plan only the "Congo Sea" were actually accomplished it would mean nothing less than opening the gates of the Dark Continent for civilization and progress.

(Originally Published in the February 1939 Issue of Marvel Science Stories)

Click to join 3rdReichStudies